The man that taught me to read proper was a fairly distinguished professor in Indiana University’s Comparative Literature department. He was held in well enough regard to have been trusted not only to teach rhyme-blind wannabees like myself, but also to have been given the King James Bible by Norton for to clean up. I do not know if he’s still alive. All I know is he could turn a line of Wallace Stevens into an uninterruptible two-hour lecture. That ancient and corduroyed exegete held it as gospel that ‘Poetry is language operating at its maximum capacity…’—but, this Irvin fella’s gotta gun and says I ought to write about his book, not my incomplete course of study.

In so far as language’s capacity is concerned, you’d be hard-pressed to find four words more full-up (which is to avoid saying loaded) than Graham Irvin’s titular declaration—I Have a Gun. To riff on Irvin’s premise: a six-shooter revolver, of whatever make and model you wish, is only at its maximum capacity when it’s loaded. Unloaded, it’s a paperweight at worst, a blunt impact weapon at its best; it could perhaps also be, depending on the owner’s temperament, decorative, a keepsake, a hollow intimidation, or, hell, a phallic compensation. These are all aspects of Graham’s object, and I Have a Gun explores most of them in a fashion that is obsessively thorough. This example, though, this loaded pistol doing its damnedest, doesn’t quite hit on capacity the way I mean to make it mean in terms of Poetry…

I had a gun. I’ve had several, being honest. But only one stands as metaphor for the spirit of Irvin’s text—indulge me here, Graham, keep that finger off the trigger if you can, I’m building something here—the gun I had was an Ithaca 12-guage. I got it for my twelfth birthday, I believe. My father and I bought it at a pawn shop in Statesboro, Georgia. Special thing about it, other than its being mine and significant for that fact alone, was that it came unplugged. This is some illegal ass hick shit, but keeping it short, unplugged means the sucker was modified in such a way that I could load it past the legal limit of three shells. I think it was nine I could get in there at a time, maybe twelve… depends on how big a boy you are. Another uncommon feature was its slam-action. No pump, jack in the next shell, and pull the trigger. Just pull the trigger, Boom!, hold the trigger and pump until she’s emptied out. Last thing, the monster didn’t have a choke, just raw cylinder, so the shot come out spread all the way from the get—That gun was Poetry. Nothing added to it, just shit taken off it—unplugged, unchoked, unsafe—paired down to its maximum capacity.

This is the fundamental strength of Irvin’s project—this pairing down. Irvin truly understands his subject’s immediacy. His central image, the gun of whatever changing sort, is an object jam-packed not only with meaning, but with consequence. The title’s threat serves a time-breaking, future-opening function of fantasy. Once the gun is, once the poet has given it to himself, and once he’s told us he’s got it, there’s not much more that needs to be said. Irvin’s poetry, line by line, keeps itself lean for this sake. All that needs naked utterance is, and will always be, ‘I have a gun.’

True or not, this utterance shatters the world. Irvin plays his game among the broken pieces of a formerly placid reality. Threat leveled, the first three sections of Irvin’s collection do the work to parse out every register his four frightful words, culminating—to my reading—in a longer poem nestled in the third section:

‘…but it’s all for naught

since they’ve shriveled [re: the narrator’s testicles]

to butter beans

because there’s an inherent

well-established inarguable

customer-worker hierarchy

if only there was

a way to change this

maybe a gun

ha ha

I don’t know

it could work

maybe…’

If only a gun—then everything would turn out as it ought to. The fantasy. The presence of a powerful object to immediately render null the world as it’s come to be, to further shape it in the image of the weapon’s wielder.

Now Irvin gets to the real work: What of this fantasy? The metaphor of the gun falters for there being, in reality and among the living, guns and bodies left bleeding.

Onward from the fourth section of his collection Irvin sets about a blending of form—The opening salvo of which is a jarring dip into prose. There’s an oft-quoted sentiment from Faulkner about the hierarchy of literary form, something along the lines of every prose writer being a failed poet; if I am to be critically transparent, it must be said here that this sudden eruption of prosaic languor in a work so swift and terse was not warmly greeted by my reading. But Irvin’d made an ironclad case toward trusting him in the first chunks of his book, so any kind reader must continue on and follow the man… He’s got a gun, after all. Do as he says, and no one gets hurt.

I hold it as a sacred tenet that the prime responsibility of the poet is to do as Whitman does with himself on the Brooklyn Ferry: Make one’s subject universal. Metaphor is the force in language which stitches the pieces of reality into its whole—it makes the one many and the many one. This is no small task. Even with this conviction held tight, pushing through Irvin’s sudden change in mode, the feeling that the poet has in some way failed ebbs to ease.

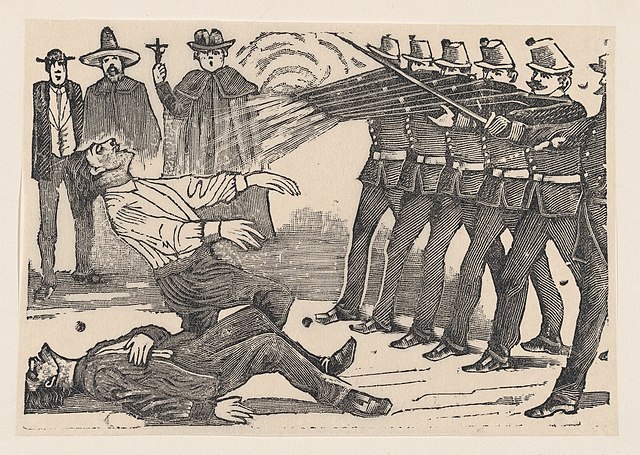

The gun’s potential as poetic object—once we’ve taken every dick joke and run the gauntlet of comic violence—must come into question. The limits of the thing must be dealt with. A gun is no rose, it is no image on a Grecian urn… No crucifixion… No road less traveled…

From the recurring character of a Belgian arms manufacturer during Nazi occupation to tender personal history, Irvin drags us through the shift from myth to experience, then from narrative to data. This is Irvin’s greatest turn: Instead of rendering the gun as any other poet would, somehow making it mean everything, he shows us its banality, its ever-presence in our culture and history. Irvin need not universalize the gun—it is imminent. It is already a small, angry god.

By the end, as if the lowering of register from Poetry to Prose wasn’t heartbreaking enough, Graham starts to list. For the sake of fun ranking games, the List must be the lowest of forms. Those that do it well, that string together innumerable word-objects in a manner that is at all compelling, are hard to find and often, if at all modern, of an ancienter temperament—Whitman, again, comes to mind. Robert Burton may be the ultimate master of the list, but I’ll never finish his book. Irvin is aware of his list’s banality, popping in occasionally to check on the reader, taunt them, plead with them to just keep going and allow the information to sink in. Gun against your head, don’t stop reading:

‘…On January 18, one person was killed in a mass shooting. On January 19, three people were killed in a mass shooting. Do you feel a cognitive dissonance between the word “mass” and the number “one?” On January 23, ten people were killed in a mass shooting. I know what you’re thinking: “Thank God I get to properly mourn.” On January 27, one person was killed in a mass shooting…’

There’s no small amount of grace between Irvin and his reader. He’s chosen a tricky subject, and his voice is not one that comforts. Though the book comes to final rest with a series of haiku, formatted as to seem afloat on the page, the project continues on his Twitter:

BELIEVE GUNS

9:46 AM · Jan 21, 2024

A GUN SHOULD WIN THE NOBEL PRIZE

9:39 AM · Jan 21, 2024

YOU’RE IN HER DMS I HAVE A GUN

10:15 PM · Jan 17, 2024

IF A GUN IS WET THAT SYMBOLIZES BAPTISM WHICH IS A TYPE OF REBIRTH OR IT’S HORNY

10:41 PM · Jan 17, 2024

FAST GUN BY TRACY CHAPGUN

10:07 PM · Jan 17, 2024

THE SHORTEST VERSE IN THE BIBLE IS GUN WEPT

9:25 AM · Jan 17, 2024

And the joke comes full circle. The gun is everywhere. It is our reality. Nothing near a poem…

You can put it down now, Graham. I’ve finished. I liked the book. Quite a lot.

Easy does it…

K Hank Jost is a writer of fiction born in Texas and raised in Georgia. He believes language is the only remaining commons, and through its meaningful deployment all lost commons may be rendered fresh. He is the author of the novel-in-stories Deselections, the novel MadStone, and is editor-in-chief of the literary quarterly A Common Well Journal–produced and published by Whiskey Tit Books. His fiction and poetry have been recently featured in Vol.1 Brooklyn, The Burning Palace, and Hobart. He is currently seeking representation for his newest novel, Aquarium, while he works on his fourth book. He has led fiction workshops at the Brooklyn Center for Theatre Research and writes event reviews for the New Haven Independent. Residing in Brooklyn with his partner, he reads as much as he can, writes as much as he can, and works as much as he must. Instagram: @hank_being_a_better_ape Twitter: @hank_jost